墨泽生灵,意蕴天地

注情于物,感情与怀,迁想妙得是也。

——周京新

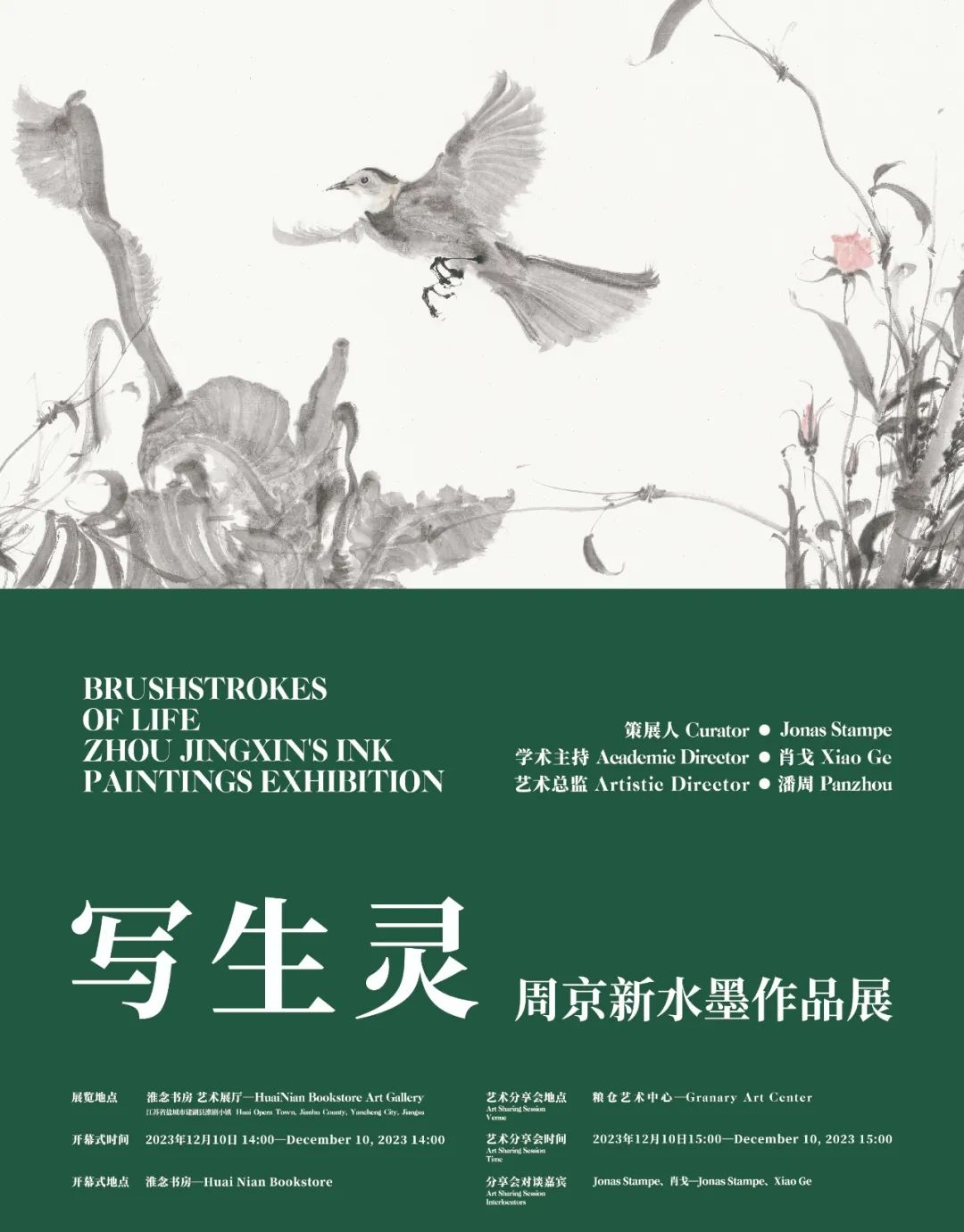

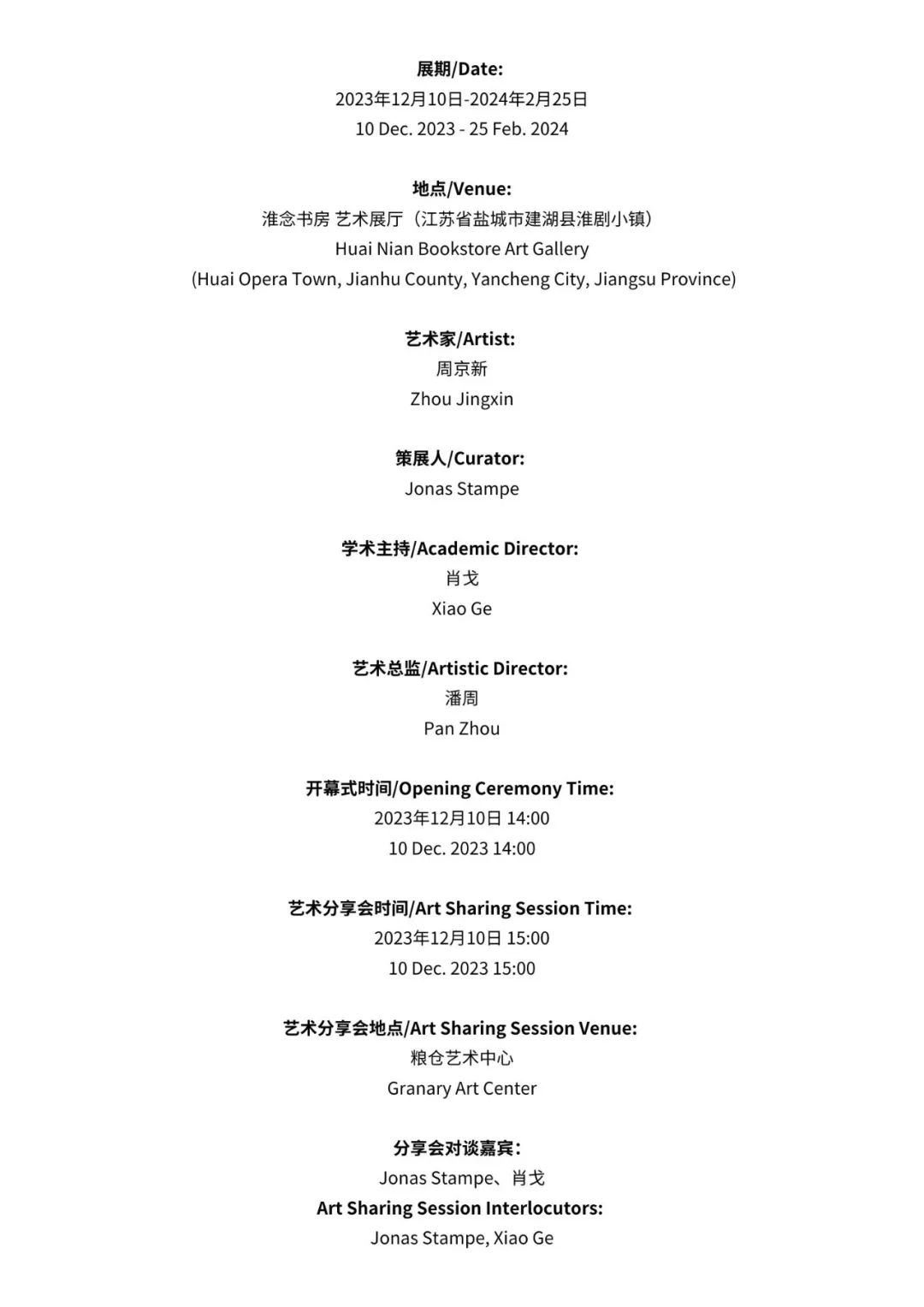

展览信息

Exhibition Information

周京新:与画为友

周京新的绘画艺术体现了强烈的直觉思维和独特的存在方式,唤起诗学和行为美学的概念。这种理论由法国哲学家保尔·瓦雷里提出,受到美国抽象行为画家哈罗德·罗森伯格的推崇。它强调,绘画的理解不仅在于形式上的呈现,如线条和色彩的组合,更在于艺术家在创作过程中的戏剧性演绎。对周京新而言,这种诗意和戏剧性超越了行为本身,成为他与水墨和纸张间的神奇融合,创造出新的现实。

周京新及其艺术表现手法中,艺术家在苏州或南京园林中的寻觅和探察阶段,对创作过程极其关键。这一过程建立在对自然的深深敬畏上,因为自然景观是他艺术作品的核心。他因其美景而执着地在特定地点、角度进行长达12天的反复描绘。这过程融合了丰富的人文元素,如十二生肖、十二年制、人体十二经络,以及阴阳相生相克理论的十二个月份。这些元素对作品至关重要。同时,创作过程也是对个人精神世界的探索,挑战自己的极限,探求新的思想观念和视觉表达方式,同时在同一主题中寻找新灵感、观察角度和交流形式。

周京新先生的现代艺术手法独特,深思熟虑,借鉴了克劳德·莫奈的创作观念。莫奈在作品如《干草堆》(1889年)、《鲁昂大教堂》(1892年)及《威斯敏斯特的伦敦议会》(1899年)中,展示了通过日出日落的光线变化来表现自然的手法。他深入挖掘自然光线效果,细腻阐述阴影、色彩和高光间的互动。这种观念和创作方式对安迪·沃霍尔也有深远影响。沃霍尔以摄影源图像为基础,探索不同形式、颜色和情感表达。周京新希望探索自己的潜力,转变审美角度,如他所说——擦亮双眼,重新审视同一场景,寻找新灵感。

周京新在其创作中始终注重创新和新颖性,他面对的主要挑战是如何运用不同的艺术手法与景色进行沟通。他坚信,要在艺术上传达新的元素,必须在思想层面上颠覆自我,并探索新的可能性。这种对创新的追求促使他强调打破传统的绘画模式,视之为艺术家进阶的关键。在他著名的“12天绘画系列”中,周京新花费大量时间进行“动态观察”,更多地是观察而非绘画,这种方法刷新了他对绘画艺术表达方式的理解。他不断尝试使用水墨在彩纸上作画,实现画作与纸张的完美融合。此外,周京新在作品中将动植物拟人化,通过思考和想象来理解它们的个性,例如,他会想象自己是一只小甲虫,从不同的视角观察植物。这种独特的观察角度使他的作品呈现出建筑与自然的和谐共存,展现了他对世界、人与自然关系的深刻理解。

周京新在其艺术创作中巧妙地捕捉并表现了时间与空间、速度与静止之间的动态平衡。他的作品,如愚园写生系列和2015年的真人大小肖像系列,展示了一种既轻盈又密集的质感,通过流动感和饱满厚重的对比,引领观众感受到时间的流动和空间的深度。周京新特有的意像虚空风格,通过虚空与实体间的对比,进一步强调了寂静与动态的交织,突出了空间的静谧和时间的流动。他的笔墨动态不仅是身心、手眼和直觉的结合,更是与时间的共舞。周京新通过想象力赋予生物和植物独特的角色和意义,创造了一种表象与现实、自然与人类感知之间复杂而微妙的联系。这些作品中的动态平衡不仅是大自然的体现,也是人类视角和情感结构的一种平衡器,展示了他对时间、速度和空间关系的深刻洞察。

周京新的作品反映了生活和艺术共同服务于人类的观念,他的画笔赋予形状和空间质感,通过毛笔的语言和格调,揭示哲学真理,探索宇宙、万物、人与自然的关系。他的作品消除对立,为人与自然间建立超凡的精神和谐,蕴含生命、希望、自然与虚无,实现天人合一。

(文/乔纳斯·斯坦普(Jonas Stampe) 2023年11月12日)

Zhou Jingxin : Being With Painting

Zhou Jingxin's way of seeing reveals a powerful intuitive thought, or more profoundly, a particular way of being with painting that evokes the notion of poïetics, or the aesthetics of doing. A theory developed by the French philosopher and poet Paul Valéry and popularised by Harold Rosenberg in relation to American abstract action painting, in which the act of painting itself is of essence. It asserts that what is important to understand about painting is not only the formal end result, the final composition of lines, colours, tones and motifs, but the drama that the artist has lived out on the paper or canvas, how it came to be what it is. For Zhou Jingxin, this poietics, this moment of drama, of painterly action, is not limited to the act itself, but extends to the time before his hands, eyes and mind magically fuse the ink-water with the paper to unite them as one and create a new reality.

The time leading up to the decisive painterly act is crucial for Zhou Jingxin and his way of being with painting, which starts with the artist looking to find a suitable motif in for instance a garden in Suzhou or Nanjing. It is a method and procedure that can take a long time since the natural scene is essential to his work, yes crucial, in that he will paint it repeatedly, from the same spot and the same angle, at times for as long as 12 days. Nothing less, nothing more, in a numerological reference to the 12 zodiac signs, the 12 years, the body’s 12 meridian pathways, and the 12 months based on the balance of yin and yang. Furthermore this procedure is based on a personal challenge, to explore his own mind and optics, to investigate if he can paint from the same place and angle, with the same perspective over and over again without repeating himself. But more importantly if he can find a new idea on the same subject, a new perspective, a new dialogue.

As we understand Zhou Jingxin's contemporary approach to painting is decisively conceptual, historically referring to Claude Monet idea to paint the same subject repeatedly in varying conditions. From the Haystacks (1889) to the Rouen Cathedral (1892) or the London Parliament in Westminster (1899) Monet painted at different moments of the day, as to explore distinctly different natural lights and atmospheres while using the same motif, perspective and visual angle, exploring in detail the effects of natural light and study the interplay of shadows, colour and highlights. A method and concept which as we know influenced Andy Warhol in his use of one photographic source image as a serial motif to explore different forms and colours and emotional articulations. Zhou Jingxin's objective for his part is to investigate his own inner potential capacity to change his visual perspective, to “polish his eyes” as he so poetically puts it, “as if it is the first time I see this scene, I have to find a new idea.”

Zhou Jingxin painting is all about concept and new ideas, making him think long and hard before going to bed at night what he was going to do the next day. The motif would still be the same, it wouldn't change from the day before, but in his need to invent a new dialogue with it, his artistic problem was how to speak to the scenery differently. How could he articulate something new in his own visual language, with his own artistic vocabulary? Zhou Jingxin realised that he needed to disrupt himself in terms of ideas, not to think about how he used to do things, how he used to paint gardens, but to find new possibilities, to think afresh, to question and change his past ideas, perspectives and forms. "I had to disrupt myself in terms of my painting method, not to perpetuate old habits, my usual ideas and painting methods". An articulated self-awareness of the need to change artistic praxis in order to develop something new, of the necessity of being with painting as a concept.

When Zhou Jingxin begins his 12-day painting series, he spends more time looking at the scene than painting it. He moves and walks around the site, looking everywhere, in all directions, to the front, above and below, to stimulate and trigger a dynamic way of seeing. His perception is sometimes influenced by visitors passing by the scene, whose voices, comments, figures and even breaths he integrates as invisible parts of the picture. Although these human details are not directly visible they are sensorially implied by Zhou Jingxin through what he calls a "dynamic observation". Perceiving, thinking and thinking again, with the critical imagination of his own vision, shaped by the aim of renewing his language and perspective, his seeing and being with painting.

Before Zhou Jingxin makes the decisive and unalterable act of no return to put ink and water on paper, to fuse them for eternity, he explores, thinks and plans, observes and thinks again, identifying himself with his subject, be it a fish or a plant. If his eyes and mind are his inner studio, the natural landscape in front of him is the trigger for his imagination and soul to articulate his innermost feelings in ever new ways. It is a work ritual of dramatic significance. Not only for the energy, concentration and focus it generates, but for the visual depth and sensitivity it articulates when the feeling and the moment are right and he begins to attack the flat white paper in front of him.

Zhou Jingxin has said that in his quest to transcend his practice, he sometimes identifies with his motifs in an anthropomorphic way, whether fauna or flora, formulating an almost animistic approach to nature. When he draws a fish, a tree or a blade of grass, he always thinks and imagines what kind of character it has. Sometimes the plant under the rock looks very good and he imagines himself as a small beetle, crouching under the plant and looking up. A position that changes his perspective of the plant and makes him paint it very high and tall. Zhou Jingxin recalls that in the later part of his 12-day painting expedition, the plant began to look like a person who kept changing clothes or identities, and after a while even began to talk to him.

Zhou Jingxin is a painter whose compositional eloquence and palette, articulated by light and softly nuanced brushstrokes in shades of grey, white and black, impress the viewer with their visual logic and rational sensitivity. Architecture and nature are two recurring motifs in Zhou Jingxin's paintings. The man-made and the natural, as a dual and dialectical signifier of the world and the coexistence of man and nature. Buildings and pavilions, or even shrines, are symbolic representations of human life and civilisation, and often placed at a distance in Zhou Jingxin's pictorial universe. These two invisible metaphors of meaning become the essential signifiers of human civilisation and nature. The two signifiers formulate a compositional relationship that is sometimes balanced and sometimes less stable, articulating a subtle but constant tension. Where architecture, as a metaphor for humanity, is represented with a slight inclination and mostly in the background of the landscape. On the other hand, nature, represented by grass leaves, trees, plants or bushes, is stable and composed in a horizontal or vertical configuration, giving stability to the four-sided pictorial space. The slightly tilted perspective of the pavilions and temples gives a sense of dynamism to the spatial composition, which is further accentuated by the foreground-background relationship of pictorial space.

Zhou Jingxin is a painter whose compositional eloquence and palette, articulated by light and softly nuanced brushstrokes in shades of grey, white and black, impress the viewer with their visual logic and rational sensitivity. Zhou Jingxin finds a dynamic balance in his expression of speed and control, expansion and contraction, movement and stillness, articulating a vitality informed by a powerful sense of constant change. They translate an open and free yet focused vision of the subject at hand into a formal vocabulary that evokes both an ancient tradition and a distinctly contemporary visual language of being with painting.

The constant mutation and evolving sublimation makes us all learn from what we see, associate and label. There is movement in nature as well as in architecture, in the painted body, which opens up new worlds and emotions of understanding. Life is a state of fleeting moments that affect our minds and hearts, they are never the same, but always in constant flux and change. What is true today is not always true tomorrow, the relativity of existence in the landscape, in the tilted pavilion, in the slender, thin plant that stands-up and grows in front of the rock and the mountain, touches our eyes and perhaps our souls. There is a fragility in the stable natural environment, a grey-black and white fluid movement that can only be felt through the slow thought of deep contemplation.

Zhou Jingxin's work is both light and dense, expressing movement with a sense of fullness and weight, as in his Yuyuan garden landscapes. At times, however, Zhou Jingxin employs the visual philosophy of intentional void, as in his series of life-size portraits (2015) or like in the series exhibited here, Swimming (2019), in which he depicts various species of fish, crabs and amphibian salamanders that inhabit our oceans. The white emptiness that surrounds the figures has a spiritual resonance, with a spatial hierarchy and philosophical meaning developed over millennia. The visual style of intentional void directs the viewer's experience through a contrast between emptiness and solid form, a formal element in Chinese painting that emphasises the value of silence, following Laozi's concept that 'great music is without sound, great form is without shape'.

The intentional void, also poetically described as 'the remaining jade', is used as a tool to open up the unlimited imagination of the viewer. An instrument of perception psychology that acts as a optical trigger and mind opener to stimulate visual participation, drawing the viewer into the picture. The intended void articulates the almighty diversity of values that permeate Chinese culture through Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism. Formulated in the Prajñāpāramitā-hrdhaya or Buddhist Heart Sutra as: "Form is no different from emptiness; emptiness is no different from form. Form itself is emptiness; emptiness itself is form. Or as Laozi put it in his Dao De Jing: "Everything on earth is born from being, but being is born from the nothingness of Dao". Zhou Jingxin reference to the deepest concepts of Chinese philosophy simply by using a deliberately empty white space that equally surrounds his figures, whether humans or fish. It is a compositional tool and a spiritual metaphor of meaning, inviting the viewer's gaze and participation while referring to a pictorial tradition of ages.

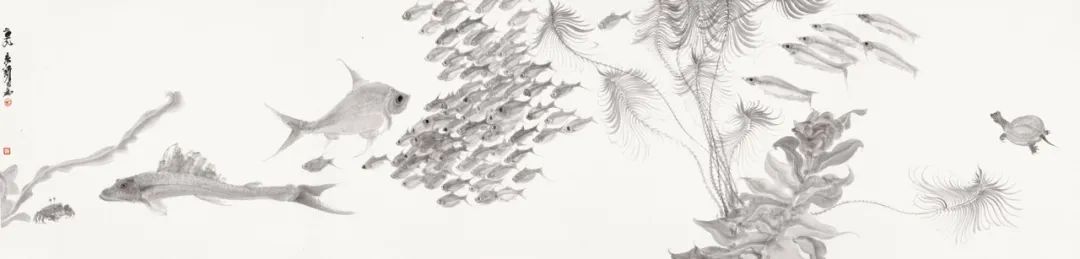

In the series exhibited here, "游", we see aquatic animals swimming in different directions within the four-sided picture frame. They swim to the right, to the left, up and down, towards and away from the viewer, and are depicted in profile, frontally or simply from above. Zhou Jingxin's freedom of perspective and optics within the emptiness of the void, the shapeless form of the element, differs from his garden paintings. Here, a similar perspective and point of view is repeated, but in another way, as if to this time around, polish our eyes. Yet both series share the same compositional eloquence and palette, articulated by light and soft, subtly nuanced brushstrokes.

These aquatic animal portraits by Zhou Jingxin are not just fish types, but are given personality through facial features that lend them an almost human expression. One of them expresses fear, another anger, while a third seems to navigate the white void with sadness. The articulation of human emotions transposed and expressed in these aquatic animal portraits demands attention. It asks the viewer to give them time, for if they are only glanced at quickly, they will appear simply as representations of the category fish and not as the characters they are actually portrayed to be. The viewer's distance and speed must be replaced by closeness and attention, in order to see detail, the small brushstroke at the corner of the mouth, or the feature that shapes the eye, the gaze, the light and the reflection that Zhou Jingxin endows each of them, in order to discover the very individual expression of each animal.

In order to fully appreciate these portraits, it is absolutely worthwhile, even necessary, to get up close and look in detail, to identify with the feeling and look into the big eyes of the different characters. Which so well articulate Zhou Jingxin's artistic talent, his empathy and ability to identify and transmit. Seen within a broader spectrum, these aquatic animal portraits appears as metaphors, as an emotional mirror of our times, of the human condition, with their sense of being lost in an environment of shapeless emptiness, alone and yet together, swimming in melancholy in all directions, seen and made visible from every possible perspective.

The dialectical dynamism of ink and brush in Zhou Jingxin's work makes it clear that he paints not only with his body and mind, his hands and eyes, his intuitive logic. He paints also with time and an profound awareness of speed, of the ephemeral moment when the ink-water blends with the paper. He paints portraits of fishes, as well as of friends, of nature and buildings, with passion and poetry, with a logic driven by an imagination in which every creature and plant has a place, a meaning and a role. Zhou Jingxin's heart-mind perception is coupled with a conceptual awareness, of seeing and being, of doing and understanding the bigger picture, inherent in the two main problems of painting: how to look at tradition and how to look at oneself. In Zhou Jingxin's work, representation and reality are never articulated as simple dependencies, but rather as a complex and subtle relationship. Truth is not always in balance, the mirror is not always made up of light waves, but also of personal emotions. Dynamic equilibrium is a given result of nature, a regulator of all humans with their wavering perspectives and tilted emotional architecture.

A continuous moment of constant transformation, life and art function in parallel with humans as receivers and transmitters. It is we and the earth that rotate, not the sun or the work of art, it is we who give meaning to art and painting in the natural speed and rotation of our understanding. This is manifest in Zhou Jingxin's work, a non-dualism that accepts and embraces contradiction, yet articulates a craft in which the brush imparts a sense of structure. Where the vocabulary and style of the brush and the ink of wood, fire and water, embodies a philosophical truth that spiritually explores the relationship between everything in the world, man and the universe, in a highly personal and individual way. Zhou Jingxin 's work removes opposites and introduces a spiritual balance of an almost metaphysical nature between man and his natural environment. There is life, there is hope, there is nature and there is the nothingness of being. Heaven and humanity are finally one.

Jonas Stampe, 12 Nov 2023

部分作品

Selected Artworks

艳惊系列之一 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2018

艳惊系列之一 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2018

艳惊系列之四 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2018

艳惊系列之四 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2018

游系列之三 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2019

游系列之三 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2019

游系列之十一 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2019

游系列之十一 纸本水墨 53x228cm 2019

(来源:艺术互动)

画家简介

周京新,1959年生于江苏南京,祖籍江苏通州。中国美术家协会副主席,江苏省文学艺术界联合会副主席,江苏省美术家协会主席,江苏省国画院名誉院长、艺委会主任,南京艺术学院教授、硕士生、博士生导师,中国国家画院特聘研究员,中国艺术研究院特聘美术创作研究员、博士生导师,江苏省政府参事,享受国务院特殊津贴。